You Can Learn to Love Yourself

This article is the second in a series, Mapping and Mastery of the Inner World: An Innovative Guide to Self-Empowerment, by Dr. Tamara Sofair-Fisch.

Eighteen months after Susan’s1 husband lost the fight to cancer, she was still in such inner pain that she was wondering if she’d ever find her old self again, and whether she would ever regain a sense of inner peacefulness. Susan, a widow in her 50s, described that the feelings of grief and being alone were just excruciating and unbearable.

Deena was married and had a dream life: a wonderful husband, healthy children, a lovely home and financial security. Yet, there were times that she felt incredibly lonely. At those times, she’d blame her husband for being inattentive and unavailable, and an argument would often ensue.

Ben, a graduate student in his mid-twenties, was agitated and bereft after his girlfriend left school for the summer. Despite her assurances that she loved him, and was committed to their relationship, Ben was consumed with fears that she would find a replacement for him.

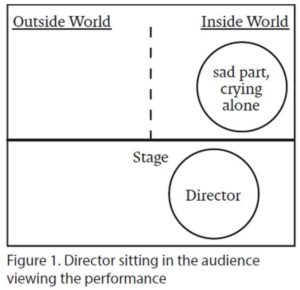

Upon initial observation, these three individuals differ in their ages, life-situations, and in just about every way from one another. Nevertheless, their inner worlds are structured very similarly. Previously, I described that we live in two worlds, the external and the inner worlds. I envision our inner worlds to function much like a play, having a director and a cast of characters that rotate in and out of being “on” the stage at any moment. I described that our inner characters have an energy that can be directed externally or inwardly. In addition to the emotional parts, we have a critic and a nurturer.

When I work with my patients, I often engage in the exercise of having them close their eyes, taking several deep breaths and having them visualize that we are sitting in the front row of an auditorium, and that the stage in front has a wall down the middle dividing the stage in two. Our imaginations are truly wonderful. I hear inner world theater descriptions that range from an inability to see anything, to viewing old school auditoriums and to seeing rooms with rich velvet curtains and plush seats.

Susan, our bereft widow visualized the inner auditorium. Once she could see the stage, I asked her to view the events of the past week on the outer world stage. She described the loneliness of eating meals by herself, spending the evening hours on her own and going to bed at night without her mate. Once she could see these events, I requested that she shift her gaze to the inner world stage. Not surprisingly, she saw herself sitting alone just sobbing.

Deena was also instructed to visualize the imaginary auditorium with the split stage. She was told to play out the scene in her home during the previous week on the outer world side of the stage. She imagined herself giving all of her love and energy to her husband and children. She saw herself cleaning, preparing meals, and taking care of the mundane chores that support the quality of our lives. When asked to shift her gaze to the inner world, Deena saw herself totally exhausted, feeling empty, lonely and sad.

When Ben engaged in the same exercise, he observed himself communicating by phone with his girlfriend on the outer world portion of the split stage. Her assurances didn’t soothe away his misery. When he shifted his gaze to the inner world, much to his shame, he saw himself crying helplessly.

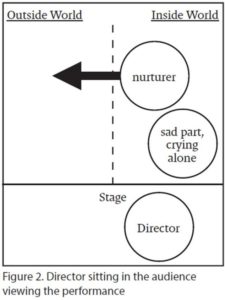

Recall that I asked each person to imagine that we were viewing the play as if we were seated in the front row of the auditorium. This permitted me to speak with each of the spectators, to find out what they thought about what they were observing on the inner world stage. In each case, Susan, Deena and Ben all expressed great sadness to see their hurt selves up on the stage. None of the three could find a way to help the bereft parts on the stage. However, when I asked each of the three how they would handle the situation if the crying part was their child, or, in Ben’s case, his girlfriend, all three knew exactly what to do. Susan expressed that she would hug her daughter, validate her feelings, and just be with her, as she experienced the pain of the grief. Deena stated that if it was her daughter, she’d hug her, validate her experience and talk to her about how it felt when she felt unappreciated by the family. Ben knew that he would hug his girlfriend and express how much he loves her.

In essence, Susan, Deena and Ben all have an intact loving nurturer part. However, their nurturer is directed outwards only. They know how to listen to, validate, and offer emotional support to people in the outer world. However, they have not learned the art of directing their nurturer inwards, so that they could truly love themselves and feel whole.

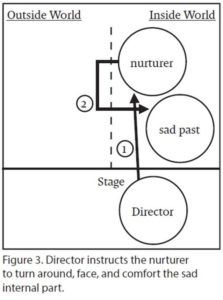

Susan was instructed to use her director (sitting next to me) to send the nurturer part into the inner world to help the bereft part that was crying on the stage. She imagined this and found her nurturer hugging her crying self, and telling her that she was not alone. The nurturer listened to the sad one, as she told of her loss and misery. The pain was still there, but Susan reported that she felt less alone and more comforted. Susan was instructed to continue practicing this exercise in the coming weeks.

Deena’s director was coached to send her nurturer on the stage. She also hugged her inner hurt part. Deena’s nurturer affirmed just how much she did each day for the family, and she was instructed to take time each day to make sure that she also took the time to provide loving care to herself. Deena’s nurturer talked with, listened to, and validated the feelings of the inner hurt part. It always amazes me just how soothing this imaginary exercise is experienced by the individuals participating in it.

Ben’s director was also instructed to send his loving part on the stage to talk with the bereft part of the self. He imagined himself hugging the bereft part, and he asked the inconsolable part why none of the re-assurances from the girlfriend were working. Emotional Ben shared a memory from childhood of how bereft he felt when his parents divorced, and his father left the family home. It became clear that Ben’s unresolved previous grief had been activated by his girlfriend’s departure. This led to working on healing the unresolved old hurt, and the development of Ben’s ability to soothe and love himself.

These three examples are summaries of cases and they don’t fully capture the emotionally powerful experience that occurs within the therapy room. I wish to stress that these skills, which are taught, do not transfer easily to daily life. In all areas of life, repetitive practice helps strengthen abilities and skills. The development of a strong, active and healthy director is no different. Thus, the constructive scenarios described above were repeated many times, before each of our individuals could rely on nurturing themselves effectively independently. We focused on developing and enhancing three aspects of nurturing: cognitive, behavioral, and emotional. The cognitive involved the words we think and say; behavioral involved staying with and being patient with the hurt part of the self; and the emotional involved communicating the feeling of love, unconditional support, and respect for the hurt part of the self. Inevitably, with repetition and practice, there is an amazing feeling of wonder, satisfaction and pride when my patients report that they used the director successfully on their own.

But, what if a person never developed an inner nurturer? Or, if the inner critic is more dominant than the inner nurturer? These topics will be explained in greater detail in future articles.